Profiles of Alberta Women

Ethel Taylor

A young Ethel (Watson) Taylor, 1926. Image courtesy of The Red Deer & District Archives. Public domain.

Personal life and education

Ethel Isabella Taylor (née Watson) was born in Gwelo, Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia) in Southern Africa in 1908. Her father was a member of the North-West Mounted Police who was drafted into military service in Southern Rhodesia before Ethel was born. He met Ethel’s mother, an upper middle-class Englishwoman, while on leave in England. The family lived in Zimbabwe and England for a few years before traveling in 1913 to Canada to settle in Fort Macleod with Ethel’s pioneer grandparents, who had established a ranch in the area in 1891.

When Ethel was twelve, her mother passed away, and her father left to seek work in the United States, never returning to his family. Ethel and her four younger siblings moved to live with their aunt, where Ethel spent much time helping with the raising of her younger siblings. Growing up, books and reading occupied much of her leisure time. Ethel’s mother had taught her to read by the time she was five, and family members provided her with books to feed her appetite. Later in life she would attribute her “probing attitude” to society to her access to books, an attitude that would inform her future volunteer and advocacy work.1 In 1928 Ethel married schoolteacher L. Hugh Taylor, with whom she had three children: Laughlin, Ron, and Mary Kay. In 1940 the family moved to Red Deer, where Ethel began a busy and lengthy career, first in community service then in politics, advocating for issues including library services and literacy.

Community service

When Ethel arrived in Red Deer, she soon became involved in a variety of community organizations, particularly women’s groups and groups dedicated to the arts. She was a founding member of the Red Deer branch of the Alberta Women’s Institutes (AWI), an organization whose first branch had been established around Lea Park, Alberta in February of 1909. At the time, AWI focused on the improvement of society through the improvement of the individual, supporting Alberta women through opportunities for education, emotional support, and social networks. During the first half of the twentieth century much of the focus was on Alberta’s rural women, who lived in the relative isolation of recently settled farms and ranches.2

In addition to the AWI, Ethel was a founding member of the Red Deer Local Council of Women, the Red Deer Quota Club, the Red Deer Allied Arts Council, and others. She served these organizations in many capacities, including as president and chairperson. She also served as a leader for the Canadian Girls in Training, and was active in Red Deer with the Red Deer Hospital Auxiliary, Red Deer Kindergarten Society, Red Deer Film Society, Red Deer Craft Centre, Red Deer Home School Association, Memorial Society of Red Deer and District, The Waska-Sues, and the Family Service Bureau. Provincially she worked with the Indian Association of Alberta, the Indian-Eskimo Association, the Alberta Drama League, and the Alberta Council on Aging.3

In 1946 the AWI ran a campaign seeking donations of books from libraries in Calgary and Edmonton. The donations were assembled into the Institutes’ library, which was kept in the Eaton’s department store to make it accessible to rural women while they shopped for their families. Ethel helped with the organization of this campaign, reflecting her belief in the importance and power of literacy for the betterment of oneself. Her dedication to libraries as a public good and service would be a theme throughout her career, both in community service and in politics.

By 1956, Ethel was serving as the library convener for the AWI, pushing the provincial government to establish a regional library program. Alberta had few public libraries compared to other provinces, and Red Deer had few compared to other cities.4 In the 1950s, the lobbying of Ethel and the AWI bore fruit, leading to both the 1956 Libraries Act and, in 1959, the creation of the Parkland Regional Library Service, the first regional library system in Alberta. However, by 1961 the region continued to lack in areas of public service including libraries, motivating Ethel to step into politics. As she said of her decision “there were no recreation facilities for women and girls, an inadequate library, no parks policy and social services here were deplorable … I decided that somebody should get in there where the decisions were made and do something.”5

Municipal politics

In 1961 Ethel ran for and won a position on the Red Deer City Council, becoming the city’s first woman alderman. She received 2,240 votes and finished sixth of seventeen candidates. Upon her election, Ethel was immediately appointed to the Red Deer Public Library Board, where she continued her championing of libraries as a public good. She faced an uphill battle, as both politicians and the public were less than enthusiastic about investing money in library services. Through an emphasis on Alberta’s poor support for libraries when compared to other provinces, Ethel was able to bring the issue of libraries to the fore and did much to advance libraries and literacy in Red Deer.

“Books for every man’s and every child’s needs in a Centennial Library – at hand for each day of each year of each century … what other centennial commemoration could afford such satisfaction to all of our citizens for today and for tomorrow? The humanities, the sciences and arts, the techniques of industry and commerce, the philosophies, depiction of places and people the gamut of imagery, and plain ‘know-how’ in diverse fields – all are accessible in a truly fulfilling library.”

With AWI, Ethel proposed the construction of a Centennial Library in Red Deer to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding of Canada. While an initial plebiscite on the proposal did not earn the necessary support, the project won approval in 1965 in a second plebiscite, after a reduction in budget. After the approval for the project, Ethel continued her work for literacy with the Library Board, continuing to push for budget, and suggesting expansions such as a regional library partnership for central Alberta.6 She also continued to work with other civic boards and organizations, including the Red Deer Twilight Homes Foundation, Red Deer Health Unit, Red Deer and District Archives Committee, G.H. Dawe Community Centre Management Board, and Red Deer and District Social Services Board.

Ethel served on the city council until 1968, at which point she left politics for a short time, before returning to win re-election to the council in 1971. She then stayed on until 1977, leaving her career in municipal politics having won re-election five times. Ethel also stepped into provincial and federal politics, running for the provincial and federal New Democratic Party, with which she was affiliated. In 1967 and 1971 she ran for the Alberta New Democrats in the Red Deer provincial electoral district, and in 1974 and 1980 she represented the federal New Democratic Party in the electoral district of Red Deer. She did not win election in any of those bids.

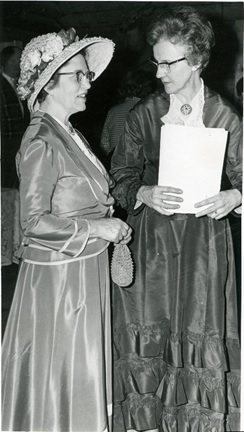

Ethel Taylor (left) and Thelma Foster. Image courtesy of The Red Deer and District Archives. Public domain.

Life after politics

Despite failing to be elected to provincial government, Ethel continued to advocate for libraries at the provincial level as a member of the Alberta Library Trustees Association (ALTA). In 1972, Ethel and ALTA spoke against the Alberta Government’s proposed changes to the 1956 Library Act. ALTA argued that the changes were insufficient, and lobbied the minster of culture, youth and recreation to initiate a comprehensive review of library services. In 1973 the government greenlit the review, and a study was conducted by the Downey Research Institute Association with the goal of reviewing library services, programs, administration, and funding. In recognition of her experience with and vocal support of libraries and library programing, Ethel was offered the position of chairman of the Downey Research Committee, which she accepted.

After only three months, the review was suspended, due in part to conflict between committee members. However, after pressure from Ethel and others who saw the commission as key to advancing library services in Alberta, the study was reinstated in 1974 and eventually produced its final report, The Right to Know. The report affirmed the individual Albertan’s ‘right to know’ as a guiding principle for development of libraries, framing library services as a public good to which all Albertans should have equal access. While change would be slow, due in part to limited awareness of the Downey study, conditions for library service in Alberta did improve, helped along by the indefatigable Ethel.

After the Downey study, Ethel continued to raise the issue of Alberta’s low funding of libraries in public forums such as newspapers and a 1976 presentation to the Alberta cabinet She also pursued other literacy projects, including a 1973 initiative that sought donations of books from libraries and individuals to First Nations and Mètis communities in Northern Alberta. Ethel’s work in her community continued until the late 1980s, when she left Red Deer for Calgary to be with family as her health began to fail. After a lifetime of literacy advocacy, community service, and political activism, Ethel died on May 24, 1989 in Calgary, Alberta.

In both quantity and quality, Ethel Taylor’s contributions to the city of Red Deer and province of Alberta are remarkable. She participated in an astounding number of local and provincial organization in arts and culture, social welfare, women’s issues, medicine, and of course literacy. Above all Ethel Taylor’s legacy is one of advocacy for literacy and library access for the people of Red Deer and Alberta. As an activist, a politician, and a citizen she worked to raise Alberta’s library services to match those of other provinces. The Red Deer Public Library (RDPL) continues today as an enduring testament to Ethel’s commitment to and advocacy for literacy in her city. The Centennial Library that she fought for is now the library’s downtown branch, serving the Red Deer community daily. Ethel’s personal collection of over 400 books also continues to bring literacy to the city, sitting as a collection at the RDPL.

Footnotes

1 Doris MacKinnon, “Just an Ordinary Person: The History of Dr. Ethel Taylor,” (student paper, History/Women’s Studies 363, Athabasca University, Athabasca, Alberta, 2004): 2, https://awmp.athabascau.ca/students/.

2 “About AWI,” Alberta Women’s Institute, 2008, http://awi.athabascau.ca/About/.

3 Michael Dawe, “Remembering Ethel Taylor’s Local Legacy,” Red Deer Express (Red Deer, AB), Oct. 19, 2011, https://www.reddeerexpress.com/columns/remembering-ethel-taylors-local-legacy/.

4 MacKinnon, “Just an Ordinary Person,” 5.

5 Ibid., 3.

6 Ibid., 8.

Student & Academic Services for The Alberta Women's Memory Project - Last Updated July 11, 2024