Profiles of Alberta Women

Jennie Stork Hill

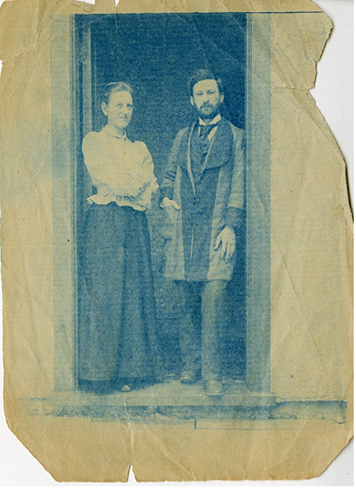

A photo of what is likely Jennie Stork Hill and Ethelbert Lincoln Hill in Guelph, Ontario, ca. 1893. Image courtesy of the University of Toronto Archives' E. Marjorie Hill fonds.

Early life and education

Jennie Stork Hill was born Jane Stork in Bolton, Ontario in 1867. In 1884 she was admitted to the University College in Toronto, the founding college of the University of Toronto. That year marked the first time the university allowed women to attend, admitting Jennie and eight other women. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1890 and began a career in teaching at the Moulton Ladies’ College in Toronto. There she taught mathematics as an assistant teacher and served as the head of the college’s mathematics department.1

“I think there ought to be a woman on the school board. About half the pupils are girls, and at least ¾ of the teachers are women. For those reasons, there should be a woman’s voice on the board.

I have no pet hobby to advance. I come to the first with an open unbiased mind ready to work for whatever is highest and best in education.

I believe our schools, first of all, ought to be sanitary. I thoroughly believe in technical training: and I would like to see the department of domestic science enlarged and extended.”

Miss Anne Merrill, ed., “A Number of Things,” Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, AB), Oct. 25, 1913.

While still in Ontario Jennie met Ethelbert Lincoln-Hill, then science master of the Guelph Collegiate Institute. The two were married on July 5, 1893 in Peel, Ontario, and soon after Jennie gave birth to their daughter Esther Marjorie Hill on May 28, 1895. A few years later, in 1907, the family moved west to Calgary, where Ethelbert took a position as the science master of a Calgary high school. Over the ensuing decades, Jennie would adopt Alberta as her own, continuing her education and putting pen to paper as a frequent poet and author in local newspapers.

Edmonton

In 1909 the family moved north to Edmonton, and Jennie embarked on a Master of Arts (MA) at the University of Alberta, earning a degree in English and History in 1911 with her graduate thesis “Gladstone and Reform.” The 1911 convocation was one of the first at the University of Alberta, and Jennie was one of only two MA graduates, as well as the only female graduate. Ethelbert also graduated from the university that year, earning a Master of Science (MSc). That year Jennie was nominated to the Senate of the university, but lost the election.2

After moving to Edmonton, Jennie involved herself in public education, serving as a schoolteacher at Victoria High School. On October 24, 1913 she was nominated by the Edmonton Local Council of Women, a group representing women’s organizations across the city, as a candidate for school trustee in Edmonton. The nomination came only a year after the city charter of Edmonton had been amended to allow certain women to vote in municipal elections and to be elected to school boards.

Jennie ran for the position on the platform of giving a voice to the female schoolteachers and children on the school board. She called for more collaboration between home life and school life, and cooperation between parents and teachers. Further, she ran a platform calling for extended manual training and domestic service classes, creation of pre-vocational schools and expansion of classes for technical school, and for cooperation between the school board and trade unions. She also spoke of the need for English education, saying “I would also like to see the English language thoroughly taught in the schools, for we cannot expect the people coming to us from all parts of Europe and even Asia to understand our government and our method of doing things unless they thoroughly understand our language and we certainly ought to attempt to give not only the children but the older ones a good training in our language.”3

The election for trustee proved to be contentious, and Jennie faced both verbal barbs and devious tactics to undermine her campaign. A controversy arose around the inclusion of a Mrs. Alice Hill on the ballot, a candidate who Jennie claimed was added to the race in a deliberate attempt to confuse voters and siphon votes from her. According to a report for the Edmonton Bulletin, the Alice Hill who was entered as a candidate did in fact exist, though she refused to speak or make public appearances, and declined to say who nominated her, lending credence to Jennie’s claims.4

“My name is Jennie Stork Hill. Just remember it when you come to mark your ballot paper. It is Jennie Hill, not Rabbit Hill or any other Hill.”

Sarah Carter, “Jennie Stork Hill and the Rancorous Campaign for Edmonton School Board Trustee in 1913,” Folio,University of Alberta, August 27, 2020, https://www.ualberta.ca/folio/2020/08/commentary--jennie-stork-hill-and-the-rancorous-campaign-for-edmonton-school-board-trustee-in-1913.html.

In the days before the election Jennie accused Dr. Frank Crang, the incumbent, of culpability in the deception, as well as with spreading false stories about her, charging him with “snake in the grass” methods. Crang denied the accusations, and in turn accused Jennie of being a woman with a “serpent’s tongue,” a barb for which he was heckled and derided by the attendant crowd.5 Ultimately the favour swayed to Jennie, and she beat out Crang with 3287 votes, despite 867 being cast for Alice Hill. Jennie assumed the role of one of four school trustees, and served in the position for two years.

In addition to her work with the public schools, Jennie involved herself in many boards and organizations while living in Alberta. She served on the board of the Royal Alberta Hospital, the finance committee of the City Hospital Board in Edmonton, and the Board of Women’s Work of the Baptist Union of Western Canada, formerly the Baptist Women’s Missionary Society of Canada. In 1923, she was one of a group of Edmontonians who organized to form what would become the Edmonton Museum of the Arts, the gallery that is now the Art Gallery of Alberta.

Jennie also served the Edmonton Local Council of Women in multiple capacities, holding the positions of corresponding secretary, convener of the committee on economics, convener of the arts and letters committee, vice-president, and as president for five years. She also contributed to the Local Council’s parent organization, the National Council of Women, serving as the national convener of economics, a capacity in which she served alongside Dr. Geneva Misener, who was the national convener for education. In the late 1920s and the 1930s, Jennie raised issues with the National Council around the employment and working conditions of married women, suggesting that the council consider “a woman’s right to judge for herself just how she shall make best use of her time.”6

Writing and poetry

While living in Alberta, Jennie also made substantial contributions to the arts and culture of the province through poetry and prose produced for the papers. She was a prolific poet, with her many poems being featured in a multitude of newspapers, both Canadian, including The Edmonton Journal, The Toronto Globe, The Victoria Daily Times, The Vancouver Sun, and The Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, and American, including The Billings Gazette, The Daily Times in Davenport, Iowa, The Buffalo Commercial, The Johnson City Staff, Battle Creek Enquirer, and the Fall River Daily Evening News. Her prowess was given recognition in Alberta through involvement in poetry and elocution contests for which she served as judge, including a 1932 elocution recitation for the Wetaskiwin school district and a poetry contest that same year sponsored by the Edmonton branch of the Canadian Authors’ Association.

Jennie Stork Hill, "Jacques Cartier: 1534-1934,” The Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, AB), May 4, 1934.

Published throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Jennie’s poetry touched on the natural, with poems about sunsets, nature, the Northern lights, chinooks, and locations like Maligne Canyon in Jasper Park, as well as the human, with poems extolling pioneers, family, peace, love, and other elements of the human experience. Jennie also produced topical poems that were published to coincide with events including Christmas, Remembrance Day, and Easter. Many of her poems also reflected the Christian faith, speaking to Christ and Christianity.

Jennie Stork Hill, "Evanescence," The Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, AB), Aug. 20, 1928.

In addition to poetry, Jennie wrote prose for newspapers in the form of book reviews and opinion pieces. She also promoted reading in Edmonton as a member and chairman of the Edmonton branch of the Dickensian Fellowship study group. The organization held events in Edmonton that included readings, music, and speakers including Jennie herself, who on one occasion spoke on the Gordon Riots in London, the subject of Dickens' 1841 work Barnaby Rudge.7

In 1936, Ethelbert retired from his position as Edmonton’s chief librarian, a position he had held for 24 years. Ethelbert, Jennie, and Esther, who by that point was a practicing architect, then moved to Victoria, British Columbia. In Victoria Jennie continued to write, producing book reviews and the occasional poem for The Victoria Daily Times. She died in 1939, only a few years after the family moved to British Columbia.

After coming to Alberta, Jennie Stork Hill made good use of her two decades in the province, and worked hard to contribute as a teacher, politician, and writer. She educated children as a schoolteacher, and gave voice to their interests, and the interests of their mothers, while serving Edmonton as a school trustee. Her contributions to the art and cultural life of the province were also numerous, including both her own writing and her promotion of art through various organizations and projects, most enduringly the undertaking that resulted in what is today the Art Gallery of Alberta.

Read more about Jennie Stork Hill

Footnotes

1 Sarah Carter, “Jennie Stork Hill and the Rancorous Campaign for Edmonton School Board Trustee in 1913,” Folio, University of Alberta, August 27, 2020, https://www.ualberta.ca/folio/2020/08/commentary--jennie-stork-hill-and-the-rancorous-campaign-for-edmonton-school-board-trustee-in-1913.html.

2 Ibid.

3 “Mayoral, Aldermanic and School Trustee Candidates Appeal to Voters,” The Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, AB), Nov. 27, 1913.

4 Carter, “Jennie Stork Hill and the Rancorous Campaign for Edmonton School Board Trustee in 1913.”

5 Ibid.

6 Naomi E. S. Griffiths, Splendid Vision: Centennial History of the National Council of Women of Canada, 1893-1993 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 185.

7 The Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, AB), Apr. 2, 1934.

Student & Academic Services for The Alberta Women's Memory Project - Last Updated November 24, 2022